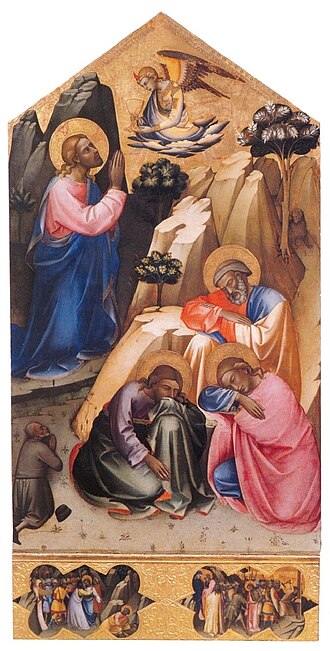

Lorenzo Monaco, Agony in the Garden

Table of Contents:

Lorenzo Monaco

Agony in the Garden (1396-1400)

Lorenzo Monaco’s Agony in the Garden has been considered an essential yet understudied work of Lorenzo’s early style in the late fourteenth Century. Painted sometime between 1396 and 1400, the scene depicts the somber moment before Christ’s betrayal and arrest. Christ kneels in prayer facing the silver chalice presented by an angel from Heaven. James, John, and Peter sleep in the foreground, failing to keep watch. To the left, a small lay donor with doffed cap genuflects in a way that replicates Christ’s pose, gazing upwards at the scene in intense prayer. A small lion makes it way down the path in the upper right, perhaps alluding to either the Evangelist St. Mark or to the commune of Florence, both of which were symbolized by a lion.

In the predella, the artist included the two scenes that directly follow the Agony in the sequence of the Passion of Christ: the Arrest of Christ and the Stripping of Christ, whereby the standing victim is forced to shed his clothing before being nailed to the cross. This latter subject was depicted in the history of Italian art and stands as an anomaly that demands explanation. The brutal scenes of the Arrest and the Stripping serve as contrasts to the tranquility in the main panel above.

The painting was moved to the Accademia museum in 1809 from its location in the monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, the former home of the artist, Lorenzo Monaco, and some have argued that the picture was intended to be seen in that space from the beginning. However, George Bent has hypothesized that the work was originally intended for a pilaster in Orsanmichele, the granary of Florence that was eventually converted into a church. Each of the major guilds owned a column there for which they commissioned works of art referencing their respective patron saints. Since St. Mark was the patron saint of the Linen Guild, and because the predella emphasizes the stripping of Christ at the crucifixion, it is possible that the guild officers commissioned this panel to represent them on its column in Orsanmichele. While the narrative sequence through the main panel and predella could suggest a possible function of an altarpiece, we can conclude from its unified compositional format that the piece was instead intended for a column.

Bibliography

Bent, George. Public Painting and Visual Culture in Early Republican Florence. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016. Pp. 216-218.

Eisenberg, Marvin J. “The Origins and Development of the Early Style of Lorenzo Monaco.” PhD diss., Princeton University, 1954. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Pp. 51-60.

Pudelko, Georg. “The Stylistic Development of Lorenzo Monaco- I.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 73, no. 429 (1938): 237-49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/867516. Pp. 238, 242.