Project Methodology

Table of Contents:

- Methodology

- The Buildings

- Art works

- Sources

- Interpretative Essays, Translations, and Transcriptions

- The Database

- Endnote

- Images

Methodology

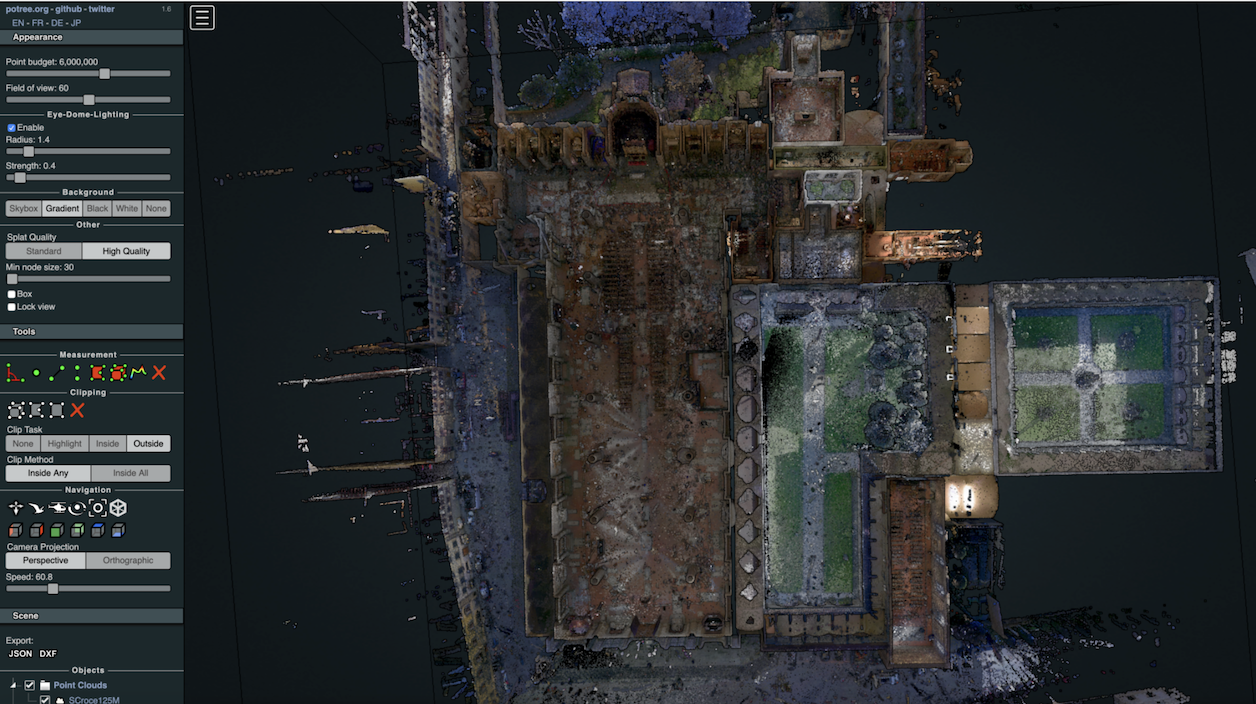

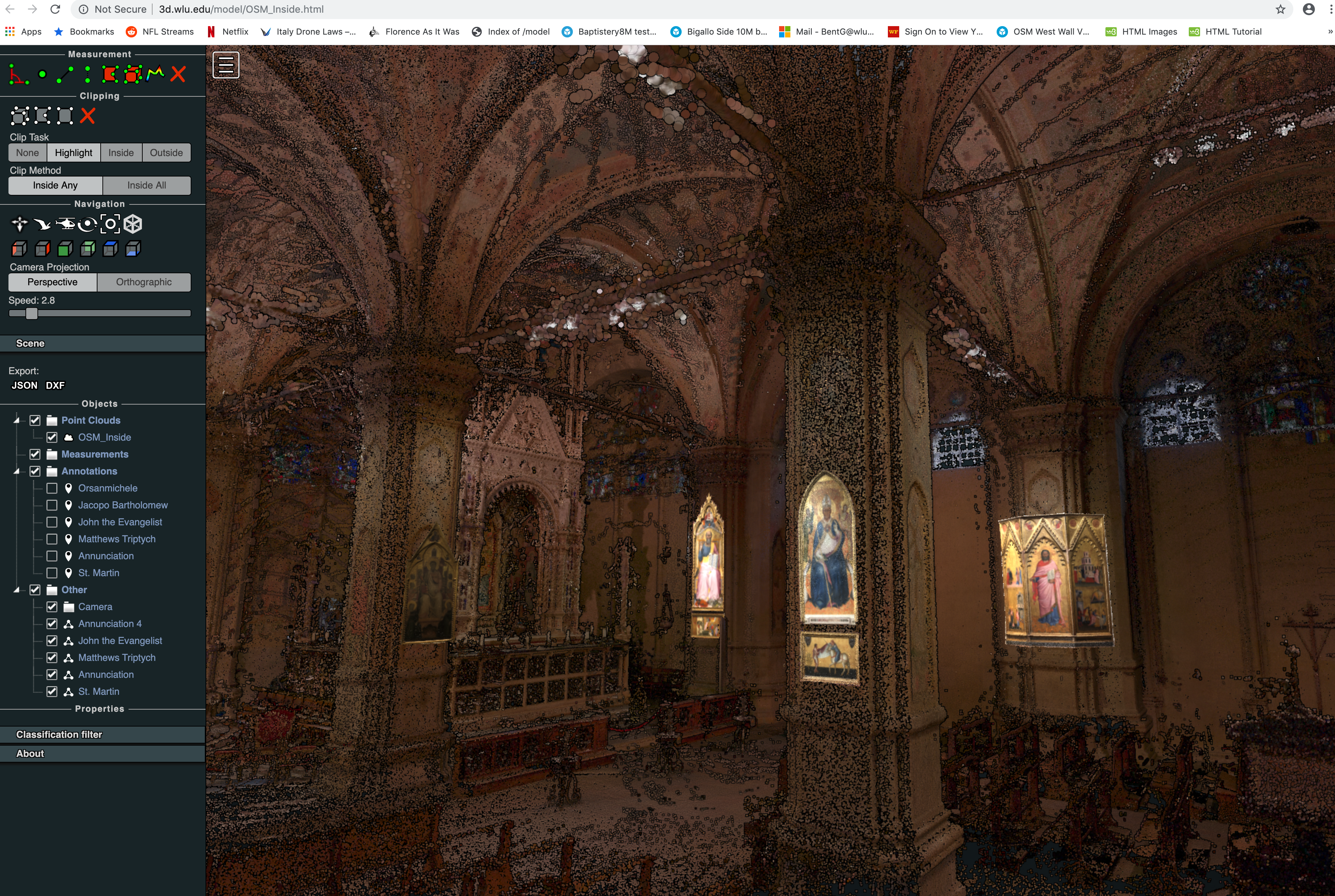

Florence As It Was has multiple aims within its broad goal of recreating selected structures in the city as they appeared in the year 1500. The pointclouds and photogrammetric models we build certainly serve their purpose as visual portals into the past, but the translations of early modern descriptions, transcriptions of contemporary documents, and the creation of a database of people, places, and things weave these images into layers of information that help us interpret what we see. Intended as a study tool (as opposed to a substitution for the real thing), this project provides users with a combination of the type of original source materials that historians of art and architecture in particular typically use when crafting scholarly works. Its multi-variances routinely force us to make choices and adhere to a list of priorities as we go.

We have progressed deliberately and with an eye toward posting the most original portions of our work first, and then filling in the gaps later on. We have concentrated much of our attention on the physically and politically challenging work of securing permissions, traveling to Florence, and then using state-of-the-art technology to scan the most important structures in the city before editing and modeling those scans so that they reflect accurately the dimensions and color patterns of those buildings.

We are guided by a number of governing principles that have never wavered since the origins of the project in 2016.

-

First, we always demonstrate our respect for the structures we scan as monuments of cultural heritage and as work environments for the staff who care for them. We touch nothing of historical value during our visits and always return modern objects to their original positions, as they may have been moved for the sake of the scanner (see fig. 1)

-

Second, we conduct our work in the spirit of collaboration with the proprietors of the buildings we scan. When we have modeled and edited a building to completion, we share the pointclouds we have made with those proprietors as .E57 files so that they may be used internally as reference guides for restoration/renovation purposes. We also encourage proprietors to use our models freely for didactic purposes on their premises (see fig. 2).

-

Third, we abide by our pledge to adhere to the scientific/academic nature of the project. We do not monetize our models and we do not permit the proprietors of buildings to use our models for profit. Only those digital humanities projects that form the consortium called Florentia Illustrata have permission to use our models, and then only if they do so in the spirit of not-for-profit academic research.

-

And fourth, we freely acknowledge that the recreated spaces we produce here are based on the research we have conducted. Decisions must be made at every turn, and at important moments we are often faced with the delicate problem of deciding which and whose research to accept and which/whose to reject. This is, we know, the most difficult part of the entire process: our reconstructions are not meant to be definitive and always reflect the scholarly opinions of their creators (see fig. 3).

The Buildings

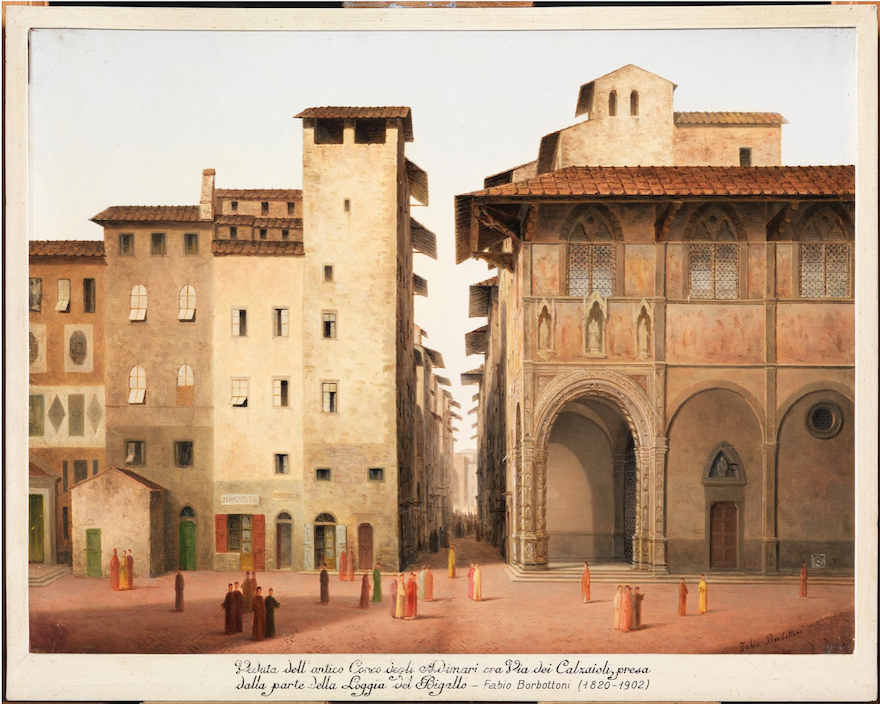

The city of Florence has changed dramatically over the centuries as fire, bombs, urban renewal projects, and general structural decay have claimed most of the buildings that once dotted its urban landscape. The Mercato Vecchio at the very heart of that landscape was demolished at the end of the nineteenth century to make way for the very Parisian-like Piazza della Republica that stands there today (see fig. 4). Fire swept through the city in 1304, destroying most of the buildings between Orsanmichele and the Arno River. The Via dei Calzaiuoli (the road through Florence that connects the Duomo in the Piazza S. Giovanni to the Palazzo Vecchio in the Piazza della Signoria) was widened at the end of the fourteenth century and shaved a few meters off the fronts of multiple buildings in the city center as a result. Most of the large stone piazze that stand before the city’s most prominent churches were either filled with houses, tombstones, or dirt circuits (see fig. 5). Nazi mines destroyed all but one of the bridges that spanned that river in 1944, along with most of the buildings that lined the avenues leading up to the famous Ponte Vecchio (see fig. 6). The flood of 1966, covered live on CBS for 24 consecutive hours, significantly damaged images and objects in disastrous ways (see fig. 7). But most common were the renovation projects by various and sundry property owners who purchased shops or apartments, realized their decrepit condition, and went about the process of ripping them apart from the inside out in the name of modernization (and commercial success – see fig. 8). We initially hoped to find ways to rebuild these lost structures, but the task proved too Herculean – even Sisyphean – for us to pursue seriously.

Still, roughly fifty structures from the late Middle Ages/Early Renaissance period survive in some form, and we have committed to scanning and modeling those for the purposes of visual recreations. The following steps are followed to complete each project:

- Contact is made via email with proprietor(s) of building. The project is described briefly; a request is made to scan the structure; dates of scanning are proposed.

- Upon receipt of a response, a Memo of Understanding (MOU) is written to reflect the interests of both parties, which always includes the explicit desire of Florence As It Was to share its data with the proprietor(s). This document will be edited and amended over time.

- Upon mutual satisfaction, dates for scanning are determined.

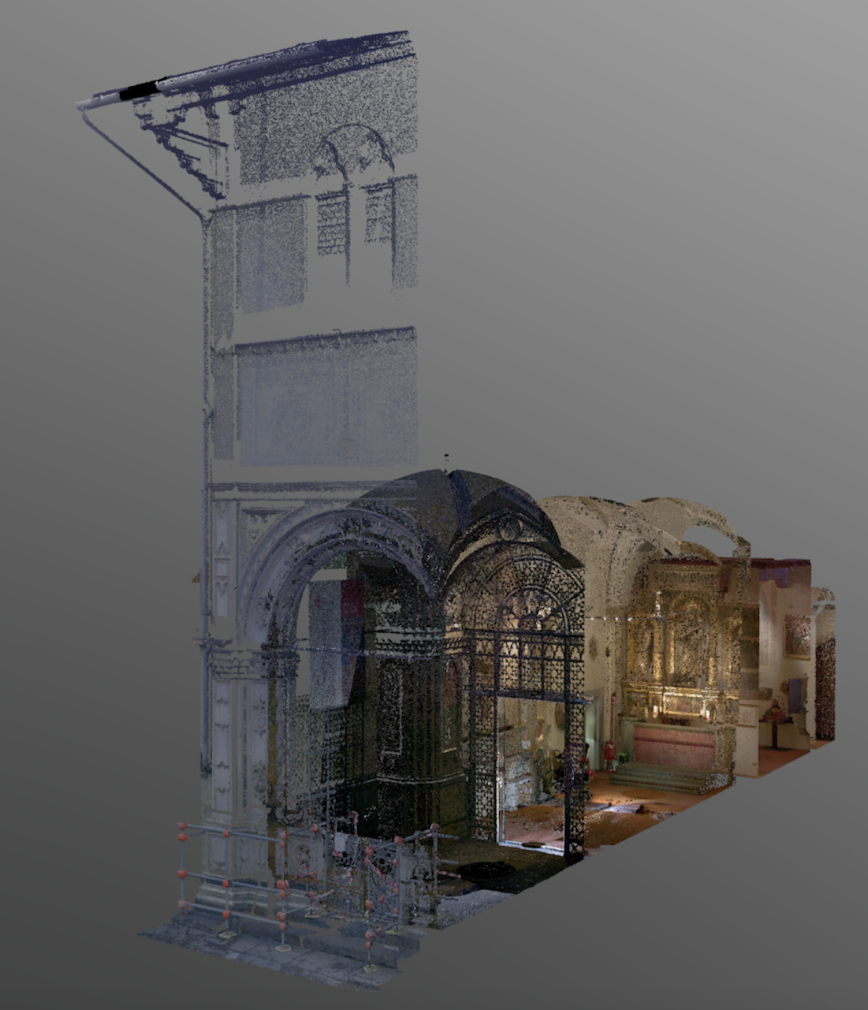

- A walk-through of the site is conducted 24 hours before scanning begins. Discussions with proprietors and their staff determine the scope of the project (i.e., which portions of the structure are off-limits, what may and may not be moved, what times of day must be avoided due to current usage, etc.). There are always – always – surprises, and most of them are of the Spectacular variety (see fig. 9).

- Scanning commences early in the morning and proceeds for 5-8 hours. Exterior walls are scanned at daybreak (see fig. 10). Heavily trafficked interior areas are scanned before or after opening hours; lightly trafficked interior areas or sections that are off-limits to the public are scanned during operating hours (see fig. 11).

- Each section of a building is scanned as an individual project, with multiple scans in each project (see fig. 12).

- The team abides by the restrictions mandated by the staff and by the limitations of the space (i.e., scaffolding, precariously high or unstable areas, security or administrative offices, etc.).

- Files are transferred electronically to the Florence As It Was Box site on the campus of Washington and Lee University. Back-up flash drives and the hard drive of the iPad used to operate the scanner retain back-up copies of every scan.

- The last day of scanning is used to fill holes, capture areas unintentionally overlooked, or address areas previously bypassed for logistical reasons.

At Washington and Lee University, files are downloaded onto local and cloud-based drives. Each individual project is linked and modeled. Individual scans are edited to eliminate evidence of human beings, automated vehicles, modern furnishings, and other random items that have no place in a fifteenth-century setting. Choices must be made when eliminating large objects that obscure wall spaces: deleting scaffolding from a chapel space, for example, results in a void in the model. Sometimes this void is better than the offending object we wish to remove, but sometimes the hole in the model is so great that alternatives must be sought (see fig. 13).

Art works

The structures modeled with LiDAR technology do not fully represent the appearance of those buildings as visitors would have known them in the fifteenth century. Styles, rituals, and the needs of users shift over time – sometimes radically and quite quickly – meaning that liturgical objects were often replaced periodically (see fig. 14). Earlier iterations of altarpieces, tombs, relief sculptures, etc. were moved to other (usually smaller and less traveled) locations in need of decorative items, which in turn were emptied of their contents in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These objects made their way into new facilities called ‘museums’ or into the hands of art dealers who sold them to buyers eager to take advantage of this new market of antiquities. As a result, Florentine buildings contain only a small fraction of the images they once held, and those images have been scattered to different corners of the globe.

Moreover, we must acknowledge the fact that perhaps as much as 70% of Florentine panel paintings from the fourteenth century have disappeared completely and were probably destroyed after their removal from their original locations. That percentage is lower for fifteenth-century images, but we must remember that our understanding of early Modern painting can never be as thorough as we would like.

Documents and descriptions of Florentine buildings help us understand where some of these items originally appeared. Reviewing texts by Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Bocchi, Ferdinando del Migliore, and Giuseppe Richa can reveal substantive information about what was where, but the reader must recognize that even these texts – published in the late 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries – describe the decorations of buildings as they appeared in those periods, rather than the one we’re interested in.

We do our best to place the images in in the buildings we have modeled that were recorded as being installed within them: but, again, we recognize that sometimes it is impossible to know precisely where small items were originally placed, how often they were moved, or why they transitioned from one setting to another (see fig. 15).

The process by which images are collected and modeled digitally replicates that of LiDAR scanning. Photographs of objects are taken from multiple angles, fed into a computer, read with software, stitched together to form 3D models, and then inserted into the point-cloud building models we have created according to the information we have gleaned from original source materials. It is our goal to visit many of North America and Europe’s finest museums to include objects spread across their collections into our site so we can further envision a more cohesive picture of Renaissance Florence.

Paintings produced by Fabio Borbottoni in the late nineteenth century have been placed in the Buonsignori Map to provide viewers with vistas seen and recorded by this amateur painter before the massive urban renewal project of the early Republic altered the city’s landscape irrevocably and intentionally to replicate the Parisian model of the era (see fig. 16). A quick comparison with photographs produced at exactly the same time by the Alinari and Brogi companies reveal the liberties taken by Borbottoni as he painted his vistas, and users should recognize that the artist was interested in capturing both the old city as he saw it and the old city as he wanted it to be: and that those two things sometimes did not correspond very closely (see fig. 17).

Any person with a smart phone or digital camera may photograph a work of art. Publishing those photographs as printed materials requires permissions from the owners of the works. The Internet is still a gray area in this regard, and Florence As It Was has delayed this phase of the project in order to understand fully its fiduciary and legal obligations.

Sources

The elimination of modern elements can be easily determined: fire extinguishers, cordon ropes, and electrical cords obviously have no place in a Renaissance building. But cutting away architectural structures to reveal earlier areas must be done carefully, always considering the original source material and scholarly interpretations that have argued persuasively for a particular appearance. The decisions about where to place models of art works that originally decorated the spaces we have scanned are equally delicate. Before making decisions to eliminate architectonic elements, we:

- communicate with the building’s staff/in-house architect to understand issues and problems on site;

- review published documents that trace construction dates, renovation projects, and artistic additions and subtractions;

- read and analyze scholarly publications dedicated to the building’s construction and decorative history, and occasionally correspond with living specialists (if possible) to corroborate our interpretations;

- consult the texts of Ferdinando del Migliore, Giuseppe Richa, Walter and Elisabeth Paatz, and any other descriptive texts that describe the space in question;

- collaborate with other digital humanities projects that may be considering the same space in the same way.

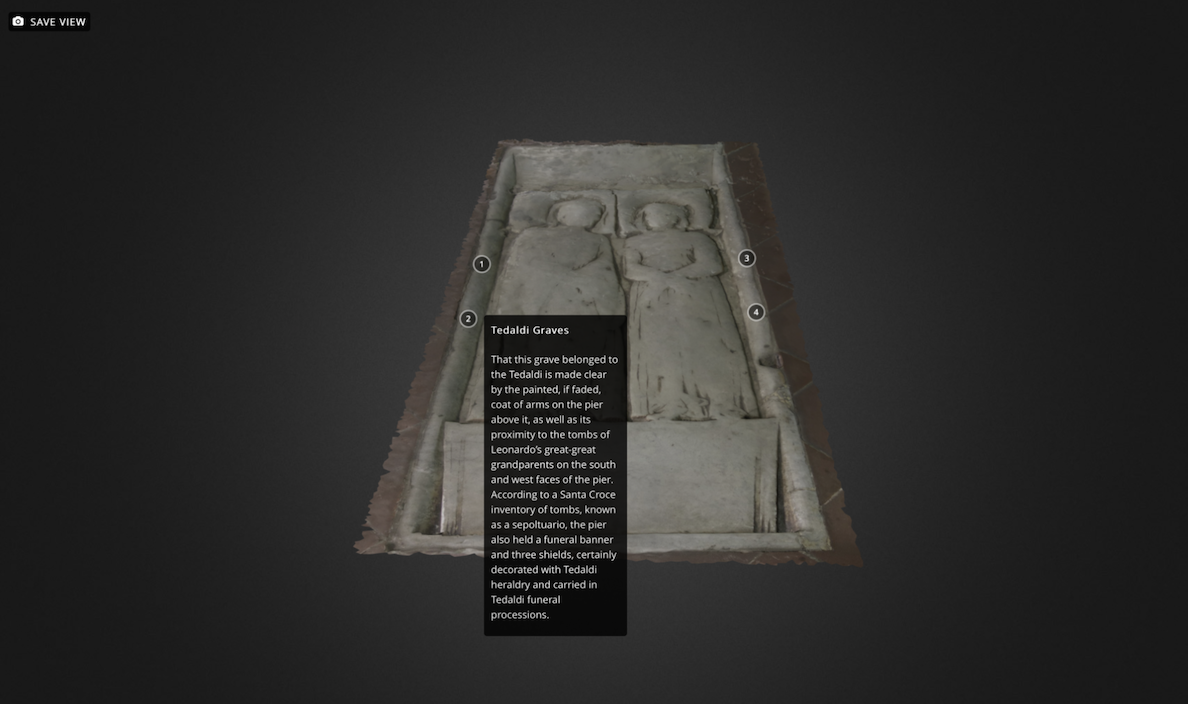

Interpretative Essays, Translations, and Transcriptions

We have insisted from the beginning that Florence As It Was exhibits informative content as well as visual interpretations of the original appearance of the city’s architectural monuments. We have also insisted that this content shall be collected and disseminated by multiple voices in a truly collaborative fashion. George Bent, an art historian of the Florentine Renaissance who has written extensively about both monastic and public art in the fourteenth century, produces some of these interpretative essays. Students at Washington and Lee University pen a majority of the others, but always with Bent’s supervision and final editorial eye: any errors in these texts are entirely his responsibility. Some members of the academic community have also volunteered to write descriptive texts about images or structures that fall within their particular area of expertise (most notably Anne Leader’s annotations of the Tedaldi Tomb in S. Croce’s nave and Mark Rosen’s essay about the Buonsignori Map of 1584 that serves as the platform for this project – see figs. 18 and 19).

Every essay and annotation that appears in Florence As It Was has been researched using current scholarly interpretations published by leading specialists of the period and place. Abbreviated references often appear at the bottom of each essay to guide readers to other published sources (usually in English) should they wish to consult them.

Descriptions of Florentine buildings guide our thinking when editing point clouds and adding photogrammetric models of art works. These descriptions have never been translated into the English language, which makes them accessible to a select group of readers. The team at Florence As It Was includes skilled German speakers who, under the tutelage of Prof. Paul Youngman, translate sections of the important encyclopedic history of the city’s churches published in the early 1950s by Walter and Elisabeth Paatz called Die Kirchen von Florenz (see fig. 20). Bent focuses on texts written by Ferdinando del Migliore in the 17th century and Giuseppe Richa in the 18th, translating them from their original Italian into English (see fig. 21). Together, these texts present readers with both an understanding of what these writers saw, what these researchers discovered, and how the interiors of Florentine buildings changed from one century to the next.

Similarly, documents published over the centuries by scholars of the period are collected together, transcribed, and then annotated. These documents are organized chronologically according to each building we model and according to projects within that building (see fig. 22). Obviously, choices must be made about which documents to include in this site: the number of published archival references to the comparatively small granary/cult center/church of Orsanmichele are so numerous as to fill the pages of an entire book, and space limitations (and copyright issues) make it impossible to include every entry here. Still, we do our best to identify key documents that help tell the story of a building’s construction, its decorations, and the people involved in the projects that made that edifice so important in the early Modern era.

The Database

Florence As It Was revolves around the structures and images that appeared before viewers and visitors to the city in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. As such, the information we include in our database pertains specifically to these topics: we celebrate the efforts of our colleagues and peers to present mappable interpretations of social, political, and economic history through the digitized datasets of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century census records, but we choose not to replicate that important work. Instead, we map the images, image-creators, patrons, subjects, materials, and chronological sequencing of art objects and architectural structures in Renaissance Florence to help users identify patterns of production and representations, networks of patronage and associations, and the gradual accretion of images in the city over time.

Supervised by Mackenzie Brooks, students have designed this database and entered information into its structure according to scholarly publications that confirm the names, places, and dates of surviving works of art known to have decorated Florentine buildings by 1500.

Endnote

Formed on the foundations of thirty years of scholarly experience in the city of Florence, this project attempts to present a thoughtful representation of an early modern city based on archival information, archaeological evidence, and decades of academic interpretation. We present reproductions and representations of standing monuments in ways that permit users to consider objects of art and architecture from angles unavailable to them in situ. We offer textual information that simultaneously educates and offers hypotheses for consideration by scholars, students, and the general public. And we provide a physical context for the images and objects that all of us gaze upon in wonder, in curiosity, and (in some cases) in rapture. None of this would be possible without the explicit cooperation and collaborative spirit of the Italian institutions whose structures and decorative items we include here, nor would we have managed to progress with such speed without the support of specific members of the Florentine art and architectural historical community who have shown their faith in us and in what we’re trying to do: to each of them individually and to all of them collectively go our sincere and heartfelt thanks.

We are enormously proud of the work we have done at Florence As It Was, the effort that scores of undergraduates have made to populate this site with important observations and information, and the results that, we believe, speak for themselves.

This ongoing project – the end of which is nowhere near in sight – will expand, improve, and surely change as the years go by. We hope you’re here every step of the way to see us through all of it.

– George Bent, August 2021

Images