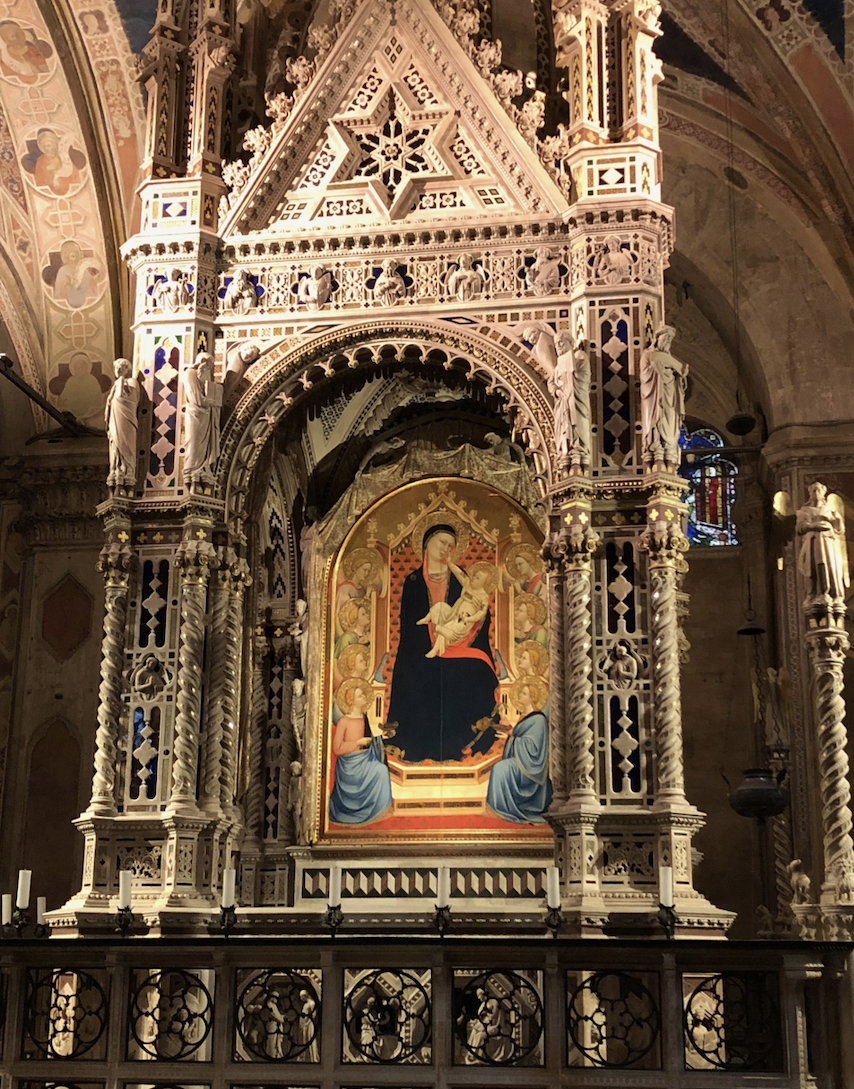

Orsanmichele, Tabernacle (Baldacchino), di Cione

Table of Contents:

Andrea di Cione, Baldacchino, 1352-59

Orsanmichele

Framing magnificently the famed miracle-working Madonna of Orsanmichele by Bernardo Daddi, Andrea di Cione’s Baldacchino articulated perfectly the mid-Trecento aesthetic that appealed to Florentine audiences of the day. A massive structure, carved in marble with sections of inlaid gold and mosaic tesserae sprinkled throughout, the tabernacle both framed the picture that, in 1365, was named the “official painting of Florence” and stood on its own as a cultural curiosity that brought in local and international viewers in droves (figure 1).

Andrea di Cione, or “Orcagna” as he was known to contemporaries, received the commission to sculpt this absolutely massive ensemble in 1352, some four years after the passing of the Black Death. The commission to replace the previous tabernacle that had stood since the second decade of the century may have been initiated by the Captains of the Confraternity of Orsanmichele as a response to the extensive criticism it had just received for the way in which they handled and then spent the windfall of profits the institution had just accepted after the wills of thousands of Florentine plague victims were opened and their bequests distributed all at the same time. Matteo Villani, in his Chronicle of Florence, vehemently condemned the captains, accusing them of embezzlement and condemning them for their selfishness. Orcagna received his commission shortly thereafter.

Orcagna designed the tabernacle as an architectonic edifice that approximates the loggia form used so frequently by confraternities across the city. A two-tiered grate surrounds the square loggia on all four sides, with each corner articulated by similarly twisted column clusters that form hefty piers from which spring the ribs of the vault (figure 2). The rounded arches provide sightlines for the miraculous painting on three sides. Pinnacles and pediments extend toward the ceiling, and serve to partially conceal a ribbed dome that may well symbolize the heavens above. Book-wielding evangelists and angels stand on these piers and columns to assert the textual and spiritual authority of the Virgin Mary.

The pedestal upon which this loggia sits has been adorned with a series of relief panels dedicated to scenes from the Life of the Virgin Mary, an appropriate subject given the presence of the painted miracle-working Madonna in the middle of the tabernacle. Among them appear the Birth of the Virgin, the Education of the Mary, the Annunciation, the Presentation of Christ, and the Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin, all of which demonstrate a similar approach to spatial flatness, volumetric mass, and gestural message.

Circling up and around the actual picture appear sets of angels who pull back a marble curtain in a manner that probably replicates the solemn ritual that was performed every time the Madonna was unveiled for privileged viewers, whereby an actual curtain was lifted up by custodians who were seated inside the back of the tabernacle, pulling on ropes unseen by those standing in the church. Increasingly during the fourteenth century, these visitors tended to be non-Florentines of high standing, as the previously open arches along the sides of the building in which the tabernacle was located were gradually walled up and the miraculous image inside was covered for its own protection.

Orcagna’s tabernacle received great acclaim almost as soon as it was completed. Only months after its installation in 1359, the artist was offered the position of Master of the Cathedral by the canons of the Duomo in the papal retreat town of Orvieto, about halfway between Florence and Rome: that endeavor lasted roughly three years, and by 1362 Orcagna was back in Florence, where he soon accepted the commission to produce a painted effigy of St. Matthew for the Arte del Cambio, or Bankers Guild, of Florence. The decision to name the miracle-working picture inside it as the official painting of the city seems to have motivated, in part, by the sumptuous sculptural loggia that Orcagna had built around it. And when Stefano Marchioni wrote his chronicle of the city in 1377, Orcagna’s s Baldacchino was the only work of art that the author bothered to mention, thus prioritizing this sculpture over the paintings by Giotto, the reliefs by Andrea Pisano, and the architecture of Arnolfo di Cambio as the image of primacy in a city filled with other logical candidates.

Bibliography

Cassidy, Brendan. “The Financing of the Tabernacle of Orsanmichele.” Source 8 (1988): 1-6.

____. “The Assumption of the Virgin on the Tabernacle of Orsanmichele.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 51 (1988): 174-80.

____. “Orcagna’s Tabernacle in Florence: Design and Function.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 55 (1992): 180-211.

Fabbri, Nancy and Nina Rutenburg, “The Tabernacle of Orsanmichele in Context.” Art Bulletin LXIII (1981): 385-405.

Kreytenberg, Gert. Orcagna (Andrea di Cione): Ein universeller Künstler der Gotik in Florenz (Mainz, 2000).

Zervas, Diane Finiello. Andrea Orcagna: Il Tabernacolo di Orsanmichele (Modena, 2006).