Mark Rosen University of Texas at Dallas

Don Stefano Buonsignori: A Brief Biography

Until recently, little was known about the life of the cartographer behind the spectacular 1584 view of Florence. Unlike many of the great late-sixteenth century cartographers, he wrote no scientific treatises, did little to publicize his own work, and never forged lasting links to local artistic and printmaking communities. The entirety of his known output was produced under the patronage of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici (ruled 1574–1587), best remembered as the patron of the Palazzo Vecchio Studiolo as well as his ill-fated second marriage to Bianca Cappello. A handful of scientific instruments—a quadrant, four polyhedral sundials, and a four-bowl Scaphe dial—in the Museo Galileo in Florence are Buonsignori’s only known objects besides his maps.

Buonsignori began work for Francesco as a replacement for the brilliant polymath Egnazio Danti, a favorite of Francesco’s father Cosimo I. In addition to publishing a dozen technical treatises and occupying a prestigious chair in mathematics at the University of Florence, Danti had steadily worked on a cycle of painted maps for a new space in the Palazzo Vecchio, the Guardaroba Medicea. Working slowly, Danti had completed 30 by 1575. For unclear reasons, Francesco fired Danti late that year and immediately installed Buonsignori to complete the space’s decoration with 23 additional maps, which he finished around 1586.

Before being brought into grand-ducal employment, Buonsignori was not known as a cartographer. His entire career, in fact, had been in religious service and administration for the Olivetan order, to which he was initiated in 1541. The Olivetans were a Tuscan-based offshoot of the Benedictine order, with their large mother church, Monte Oliveto Maggiore, located in the Sienese foothills. The order had two major church compounds in Florence: San Miniato al Monte, the famed Romanesque church and cloister facing the city from a hilltop southeast of the city center; and San Bartolomeo a Monte Uliveto, an Oltrarno complex situated in the hills above the San Frediano neighborhood. The self-portrait of Buonsignori holding a triangulation tool at the bottom of the view of Florence positions him very close by San Bartolomeo, which in fact was where he lived from 1576 until his death in 1589.

Although no baptismal record has been found, Buonsignori was constantly identified in the order, and signed his maps, as Florentinus—a Florentine. Monks were usually initiated at the age of 18, meaning that he was probably in his early 60s when he made his bird’s-eye view of Florence. Because the Olivetans customarily asked monks to rotate from convent to convent (most of which were in Tuscany), Buonsignori had spent little of his adult life actually based in Florence before 1575. But when Grand Duke Francesco, pleased with Buonsignori’s works on the Guardaroba maps, entrusted him with the plan to create the first large-scale view of Florence since the Francesco Rosselli-designed View with a Chain from a century earlier, Buonsignori seized upon the opportunity.

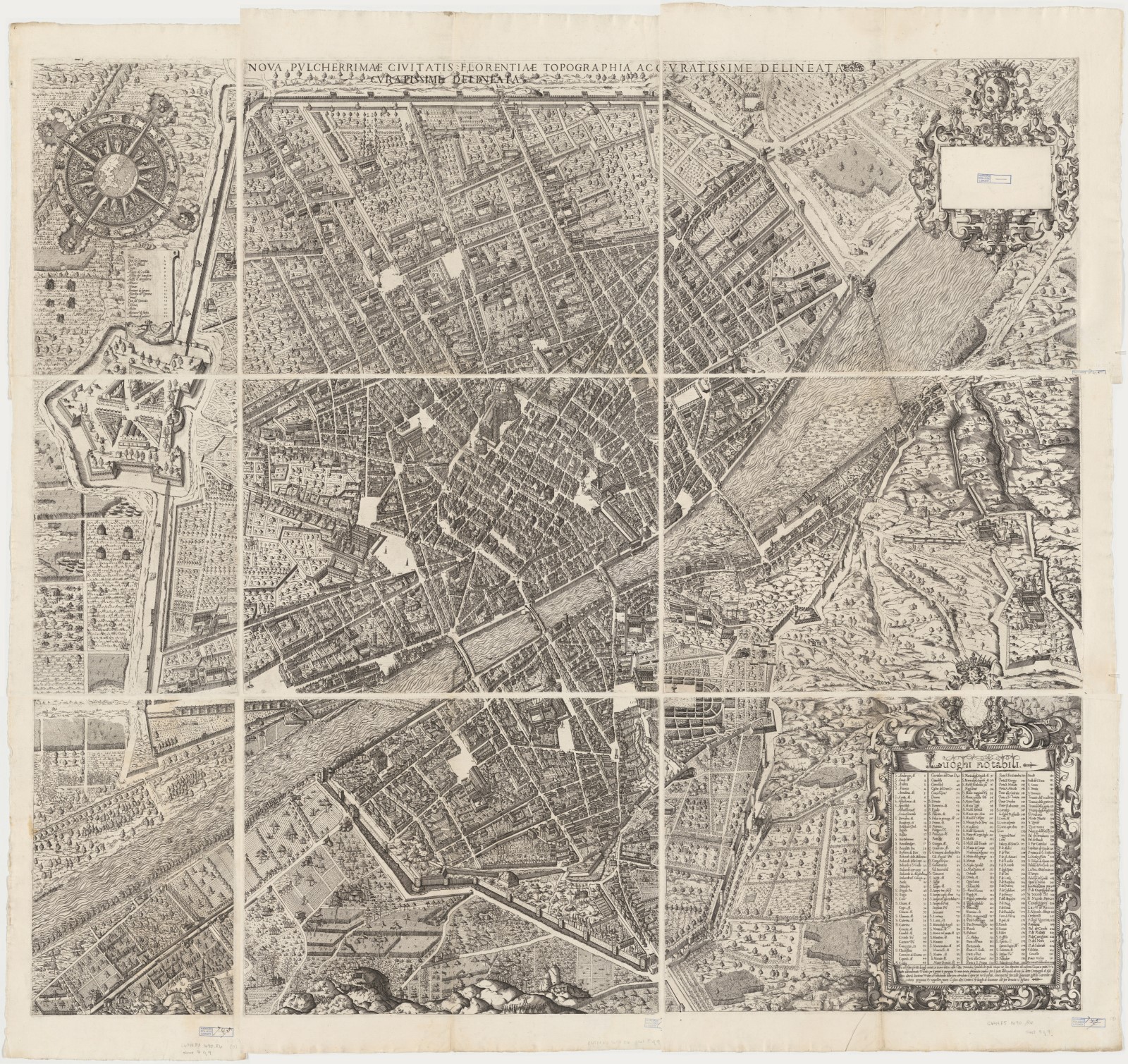

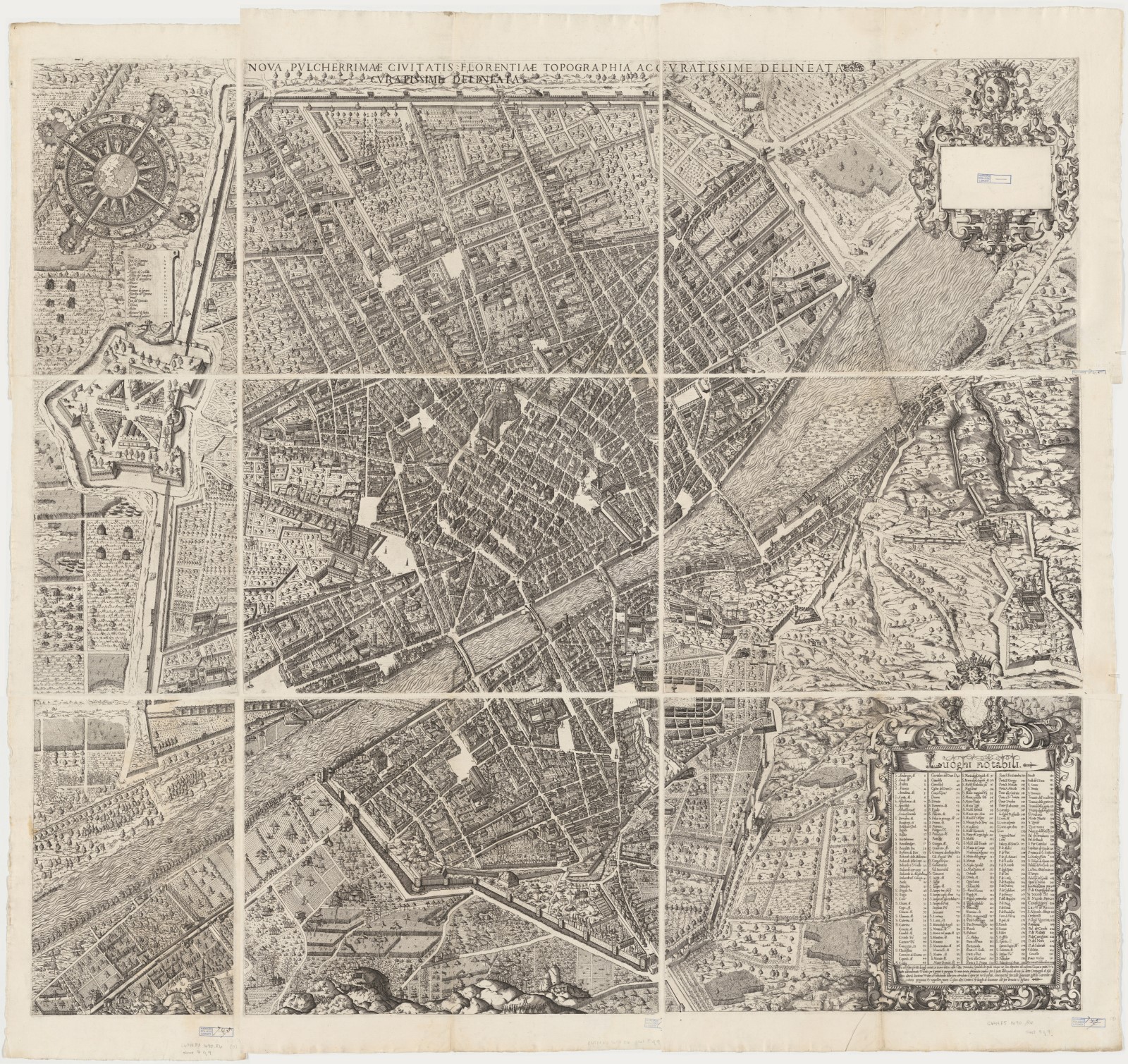

Beyond his Guardaroba maps, Francesco commissioned from Buonsignori two new maps of his territories, the Dominio Fiorentino and the Dominio Senese, both of which were printed in 1584 and circulated widely (the Fiorentino would appear in a number of editions of Ortelius’s atlas published after 1601). Those two maps, based on existing prototypes, were far less significant productions than the nine-sheet bird’s-eye view of Florence published the same year: Nova pulcherrimae civitatis Florentiae topographia accuratissime delineata. Buonsignori’s comprehensive 125 x 138 cm view was engraved in copper by the goldsmith Bonaventura Billocardo and contained a dedication praising not only the beauty of the city but also the beautification of it by Grand Duke Francesco and his ancestors. The legend identifies 225 buildings and monuments, far surpassing the detail of any previous map of the city.

Buonsignori’s last major project was a small cycle of three frescoed wall maps for the Stanza delle Matematiche, a new room on the top floor of the recently completed Uffizi. Two of these frescoes, of the Tuscan and Sienese terriories, took as their foundation Buonsignori’s recently printed maps of those regions. A third map of the island of Elba rounded out the sequence. The painter Ludovico Buti translated Buonsignori’s designs to fresco in 1588–89, while Buonsignori applied the maps’ gold lettering himself. He died soon after and was buried in the church of San Michele e Gaetano in Florence’s Piazza Antinori.